-40%

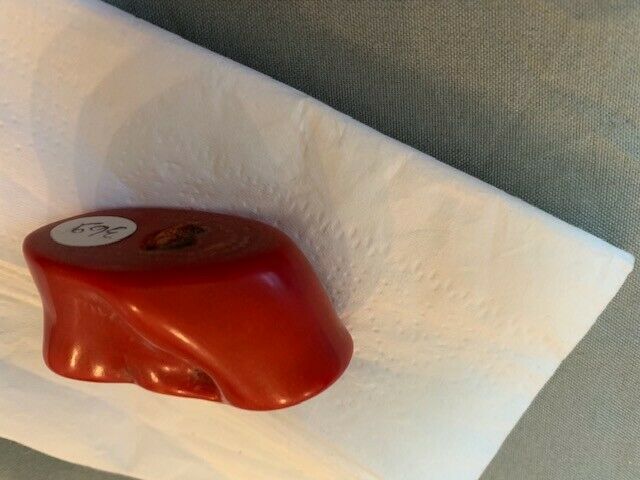

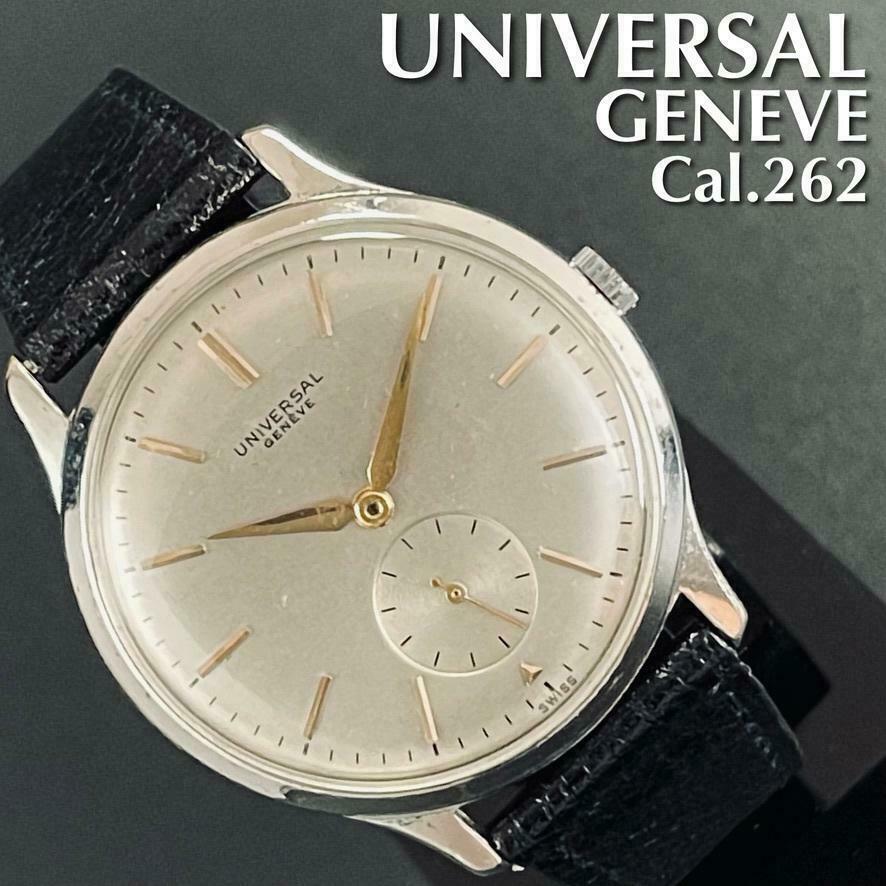

West African Manilla Bronze Trade Bracelet Money,Associated With The Slave Trade

$ 14.78

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

African Slave Trade Manila Ring. Also known as African bracelet money. These copper/bronze rings where produced for the purchasing of slaves on the Ivory Coast from the mid 15th century to the 19th century.Background info:

Manilla: The Former Currency of West Africa

SEPTEMBER 12, 2018

/

S&C ETC.

Used in West Africa, Manillas were a form of money, usually made of bronze or copper. They were produced in large numbers in a wide range of designs, sizes and weights. Originating before the colonial period, perhaps as the result of trade with the Portuguese Empire, Manillas continued to serve as money and decorative objects until the late 1940s and are still used as decorative objects in some contexts.

The name manilla derives from the Spanish word for ‘bracelet’ manella, the Portuguese for ‘hand-ring’ manilha, or after the Latin manus (hand) or from monilia, plural of ‘monile (necklace). The earliest use of manillas was in West Africa, as a means of exchange they originated in Calabar. Calabar was the chief city of the ancient southeast Nigerian coastal kingdom of that name. It was here in 1505 that a slave could be bought for 8–10 manillas, and an elephant’s tooth for one copper manila. They were also in use on the Benin river in 1589 and again in Calabar in 1688, where Dutch traders bought slaves against payment in rough grey copper armlets which had to be very well made or they would be quickly rejected.

Two different variants of manilla

Africans of each region had names for different variety of manilla, varying locally. They were often valued differently, and were notoriously particular about the types they would accept. Manillas were often differentiated and valued by the sound they made when struck.

For example, a report in 1856 by the British Consul of Fernando Po, lists five different patterns of manillas in use in Nigeria. The Antony Manilla is good in all interior markets; the Congo Simgolo or ‘bottle-necked’ is good only at Opungo market; the Onadoo is best for Old Calabar, Igbo country between Bonny New Kalabari and the kingdom of Okrika; the Finniman Fawfinna is passable in Juju Town and Qua market; but is only half the worth of the Antony; and the Cutta Antony is valued by the people at Umballa.

Sometimes distinguished from manillas mainly by their wearability are a large number of regional types called ‘Bracelet’ monies and ‘Legband’ monies. Some are fairly uniform in size and weight and served as monies of account like manillas, but others were actually worn as a display of wealth. The less well off would mimic the movements of the wealthy who were so encumbered by the weight of manillas that they moved in an awkward fashion.

By the early 16th century Portugal was participating in the slave trade for bearers to carry manillas to Africa’s interior, and gradually manillas became the principal money of this trade. The Portuguese were soon over-shadowed by the British, French, and Dutch, all of whom had labor-intensive plantations in the West Indies, and later by the Americans whose southern states were tied to a cotton economy. A typical voyage took manillas and utilitarian brass objects such as pans and basins to West Africa, then slaves to America, and cotton back to the mills of Europe. The price of a slave, expressed in manillas, varied considerably according to time, place, and the specific type of manilla offered

Copper was the “red gold” of Africa and had been both mined there and traded across the Sahara by Italian and Arab merchants. It is not known for certain what the Portuguese or the Dutch manillas looked like. From contemporary records, we know the earliest Portuguese were made in Antwerp for the monarch and possibly other places, and are about 240 millimetres (9.4 in) long, about 13 millimetres (0.51 in) gauge, weighing 600 grams (21 oz) in 1529, though by 1548 the dimensions and weight were reduced to about 250 grams (8.8 oz)-280 grams (9.9 oz). In many places brass, which is cheaper and easier to cast, was preferred to copper, so the Portuguese introduced smaller, yellow manillas made of copper and lead with traces of zinc and other metals.

Portuguese traders imported 287,813 manillas from Portugal into Guinea via the trading station of São Jorge da Mina between 1504 and 1507. As the Dutch came to dominate the Africa trade, they are likely to have switched manufacture from Antwerp to Amsterdam, continuing the “brass” manillas, although, as stated, we have as yet no way to positively identify Dutch manillas. Trader and traveler accounts are both plentiful and specific as to names and relative values, but no drawings or detailed descriptions seem to have survived which could link these accounts to specific manilla types found today. The metals preferred were originally copper, then brass at about the end of the 15th century and finally bronze in about 1630.

A class of heavier, more elongated pieces, probably produced in Africa, are often labelled by collectors as “King” or “Queen” manillas. Usually with flared ends and more often copper than brass, they show a wide range of faceting and design patterns. The fancier ones were owned by royalty and used as bride price and in a pre-funeral “dying ceremony.” Unlike the smaller money-manillas, their range was not confined to west Africa. A distinctive brass type with four flat facets and slightly bulging square ends, ranging from about 50 ounces (1,400 g)-150 ounces (4,300 g), was produced by the Jonga of Zaire and called Onganda. Other types include early twisted heavy-gauge wire pieces (with and without “knots”) of probable Calabar origin, and heavy, multi-coil copper pieces with bulging ends from Nigeria.

In Nigeria, the Native Currency Proclamation of 1902 prohibited the import of manillas except with the permission of the High Commissioner. This was done to encourage the use of coined money. Manillas were still in regular use however and constituted an administrative problem in the late 1940s. As well, in many places, a deep bowl of corn was considered equal to one large manilla and a cup filled with salt was worth one small manilla. Although manillas were legal tender, they didn’t do well against British and French West African currencies and the palm-oil trading companies manipulated their value during the market season.

The British undertook a major recall: “operation manilla” in 1948 to replace them with British West African currency. Only Okpoho, Okombo, and abi manillas were officially recognised and they were ‘bought in’ at 3d., 1d. and a halfpenny respectively. 32.5 million Okpoho, 250,000 okombo, and 50,000 abi were handed in and exchanged. A metal dealer in Europe purchased 2,460 tons of manillas, but the exercise still cost the taxpayer somewhere in the region of £284,000. With over 32 million pieces bought up and resold as scrap, the campaign was largely successful. The manilla than ceased to be legal tender in British West Africa on April 1, 1949 after a six-month period of withdrawal. It was still legal for people to keep a maximum of 200 for ceremonies such as marriages and burials.

A variant form of manilla, decorated with a native design

Internally, manillas were the first true general-purpose currency known in West Africa, being used for ordinary market purchases, bride price, payment of fines, compensation of diviners, and for the needs of the next world, as burial money. Cowrie shells, imported from Melanesia and valued at a small fraction of a manilla, were used for small purchases. In regions outside coastal west Africa and the Niger river a variety of other currencies, such as bracelets of more complex native design, iron units often derived from tools, copper rods, themselves often bent into bracelets, and the well-known Handa (Katanga cross) all served as special-purpose monies. As the slave trade wound down in the 19th century so did manilla production, which was already becoming unprofitable. By the 1890s their use in the export economy centered around the palm-oil trade. Many manillas were melted down by African craftsmen to produce artworks. Manillas were often hung over a grave to show the wealth of the deceased and in the Degema area of Benin some women still wear large manillas around their necks at funerals, which are later laid on the family shrine. Gold manillas are said to have been made for the very important and powerful, such as King Jaja of Opobo in 1891.